The British Museum has on display one of the copper plates which Sir Joseph Banks commissioned to be engraved for his planned ‘Natural History’ of the Endeavour voyage. I’m grateful to Sarah McDonald (@Artboretum), Heritage Collections Manager at the RHS Lindley Library (dream job, or what?), who re-tweeted the intriguing possibility that Mrs Delany had been inspired to create some of her famous and botanically accurate cut-paper flower images by Banks’ project.

The British Museum has on display one of the copper plates which Sir Joseph Banks commissioned to be engraved for his planned ‘Natural History’ of the Endeavour voyage. I’m grateful to Sarah McDonald (@Artboretum), Heritage Collections Manager at the RHS Lindley Library (dream job, or what?), who re-tweeted the intriguing possibility that Mrs Delany had been inspired to create some of her famous and botanically accurate cut-paper flower images by Banks’ project.

This was a great opportunity to renew acquaintance with two of my heroes. Mary Granville (later Mrs Pendarves, later Mrs Delany) was born in 1700 into the minor aristocracy. I have written very briefly about her life here, but to get the full flavour of this intelligent, spirited and well-connected woman from her teenage years to her old age, you should (must, I would urge!) read the six volumes of her autobiography and letters, edited by her great-great-niece, Lady Llanover (1802–96), and published in 1861–2.

Mrs Delany is sometimes described as having begun her paper-cutting at 72, but she clearly didn’t: she describes her cutting-out of paper flowers and birds as a pastime in her childhood, and there is an admiring reference by one of her correspondents to ‘the famous chimney-piece’ which she had completed for a friend’s house: apparently a frieze of silhouettes of classical or Etruscan figures. She was also renowned in her circle for her embroidery designs, and was evidently a well-known and accomplished craftswoman/artist. The famous account to her niece of the commencement of her ‘paper mosaick’ collection of botanical studies in October 1772 indicates that she had decided (with the encouragement of her friend and patron the duchess of Portland) to use her existing skills to a scientific rather than ‘merely’ decorative end. But was she impelled to this by the opportunity arising from the accumulated botanical specimens of Sir Joseph Banks?

Banks (1743–1820), aristocrat, botanist and great enabler of scientific endeavour from the 1770s to 1820, returned from his voyage on the Endeavour (Lieutenant James Cook, commander) with specimens of everything from plants to birds to minerals, many of them already painted by his artist, Sydney Parkinson, who, alas, had died at sea on the voyage home.

On 17 December 1771, Mrs Delany wrote enthusiastically to her brother Bernard Granville about a visit she had made with the duchess: ‘We were yesterday together at Mr Banks’s to see some of the fruits of his travels, and were quite delighted with paintings of the Otaheite plants, quite different from anything the Duchess ever saw, so they must be very new to me! … Most of the views Mr Banks and Dr Solander brought over were gone to be engraven for the history of their travels to come out next year; the Natural History will not come out till three years hence, that is, not till they return again.’ (Banks was planning to accompany Cook on a further voyage: this did not in fact happen, and Banks’ own journal of the 1768–71 voyage was not published until 1896.) On 18 December, Delany refers to the same visit in a letter to her niece Mary Port: ‘a charming entertainment of oddities, but not half time enough’.

But on 19 November, she had written (from Bulstrode, the duchess’s Buckinghamshire seat) to her niece that Banks and Solander were ‘preparing an account of their voyage … but the Natural History will be a work by itself, entirely at the expense of Mr Banks, for which he has laid by ten thousand pounds. He has already the drawings of everything … that were remarkable; the work to be set in order, that is, the history written by Mr Hawksworth, under the inspection of Mr Banks and Dr Solander; it will hardly come out in my time, as it will consist of at least fourteen volumes in folio.’ It sounds from this as though Solander (who also worked as an adviser/curator to the duchess), or possibly Banks himself, had invited the duchess, a famous natural historian and collector, and her companion to visit and see the specimens next time she was in town?

Delany was not wrong in suspecting that the ‘Natural History’ would not come out in her lifetime: the so-called ‘Banks Florilegium’ was not published in full until 1990. The first setback was the death of John Hawkesworth in 1773 (after publishing a controversial account of the voyage); meanwhile, Banks hired first five watercolour artists to copy Parkinson’s drawings and sketches, then (over a period of thirteen years) eighteen engravers to create copper plates from which the illustrations could be printed. He left 743 plates on his death to the British Museum, some of which were issued in black-and-white in the early twentieth century. It was not until the British Museum and Alecto Historical Editions went into collaboration in 1980 that a run of 100 sets was printed.

Meanwhile, as the engraving progressed, proofs were taken of the plates: some were sent to Linnaeus, who was apparently sufficiently impressed that he named a plant brought back from the Endeavour voyage as ‘Banksia’ in 1782.

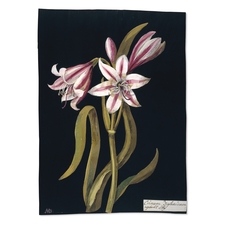

So it is possible that the duchess and the Bulstrode circle also saw proofs. But Mrs Delany had undoubtedly also been influenced by her knowledge of the paintings of Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708–70), the German botanical illustrator who numbered the duchess among his British patrons. She herself owned some of his paintings, ‘done on vellum, from rare plants at Bulstrode, and it is impossible to describe the perfection of the drawing, colouring, and individual texture given to the leaves and flowers of each plants’.

Ehret’s taro plant, Colocasia esculenta, bursting from its frame. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

(Lady Llanover applied to Sir William Jackson Hooker for information about Ehret, and as well as providing a potted biography of the artist, he reported that his own copy of the famous Trew and Ehret’s Plantae Selectae (published between 1750 and 1773) had previously been owned by the duchess.)

It is known that, in the vast majority of cases, Mrs Delany created her collages from the model of a living plant. Many, both native and exotic, were available in the famous Bulstrode gardens, and as word grew of her self-imposed task, friends and acquaintances supplied more specimens: George III and Queen Charlotte were keenly interested in the project, and plants were sent to her from Kew (at this time being developed under Banks’ supervision as a botanical garden).

Banks had the highest respect for Delany’s skill: her cut-outs (according to Lady Llanover’s editorial note) ‘were admitted by Sir Joshua Reynolds and all the best judges … to be unrivalled in perfection of outline, delicacy of cutting, accuracy of shading and perspective, and harmony and brilliancy of colours; while at the same time they were the admiration of botanists such as Sir Joseph Banks, Dr Solander, etc. etc. Indeed, Sir Joseph used to say that Mrs Delany’s representations of flowers “were the only imitations of nature that he had ever seen, from which he could venture to describe botanically any plant without the least fear of committing an error”’.

So though these various links and cross-references don’t provide direct proof of that Banks’ engravings directly propelled Mrs Delany into her ‘paper mosaick’ project, there is ample evidence that each knew of what the other was doing, and of the respect in which each held the other.

Caroline

Pingback: Names | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Object of the Month: February | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Plant of the Month: April 2017 | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Object of the Month: April 2017 | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: The Unusual Grand Tour of Sir J.E. Smith | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: The Mustard Plant of the Scriptures | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: The Legacy of Sir J.E. Smith | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Burkat Shudi | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: The Chelsea Physic Garden | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: William Turner, Naturalist | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: The Artichoke | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Plant of the Month: March 2019 | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Popinjays | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: The Pliny of Switzerland | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Plant of the Month: September 2020 | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Anna Maria Garthwaite | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: A Lost Museum | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Virtual Knowledge | Professor Hedgehog's Journal