A mostly self-taught polymath who knew everyone there was to known for two-thirds of the nineteenth century, banker, philanthropist, Member of Parliament, archaeologist, anthropologist, entomologist, geologist, best-selling author, slight eccentric (see pet wasp, and teaching poodle to read, below) and saviour of the Avebury megalithic site for the nation.

A mostly self-taught polymath who knew everyone there was to known for two-thirds of the nineteenth century, banker, philanthropist, Member of Parliament, archaeologist, anthropologist, entomologist, geologist, best-selling author, slight eccentric (see pet wasp, and teaching poodle to read, below) and saviour of the Avebury megalithic site for the nation.

Any of the above would be a good reason to remember the name and achievements of Sir John Lubbock, first Baron Avebury, but he is best known today for his driving through Parliament the bill to establish the first secular public holiday – the early (now late) August Bank Holiday Monday became very quickly known as St Lubbock’s Day after it was instituted in 1871. (Easter Monday, Whit Monday and Boxing Day, all of which followed existing church festivals, were made Bank Holidays at the same time.)

John Lubbock, from the frontispiece to Volume 1 of Hutchinson’s biography.

The eldest son of Sir John William Lubbock (1803–65), a banker and distinguished astronomer, John Lubbock was born in 1834 and died of pernicious anaemia in 1913. Apart from four years at Eton between 1845 and 1848, he received little formal education. However, his informal education was spectacular: as he described later, ‘My father came home one evening in 1841, quite excited, and said he had a great piece of news for me. He made us guess what it was, and I suggested that he was going to give me a pony. “Oh,” he said, “it is much better than that: Mr Darwin is coming to live at Down .” I confess I was much disappointed, though I came afterwards to see how right he was.’

The Lubbock family’s country home, High Elms, near Bromley, Kent, in the 1840s.

The two families lived about a mile apart, and Darwin was in some respects a second father to the young John, getting his father to buy him a microscope and encouraging and guiding his early interest in natural history, which of course played no part in his formal education. His own father coached him in mathematics, but this was not a wild success: ‘My father’s mathematical genius was in some respects a disadvantage. He could not see difficulties where I did, and though very patient would often at last say in despair, “Well, if Newton does not make it clear to you, I am afraid I cannot. We must go on.”’

Sir John William Lubbock in 1860.

In 1849, John began work: ‘when I was nearly fifteen, my father’s two partners being in bad health, he had to choose between taking another or bringing me at once into the Bank to assist him … and in 1849 I began business.’ The possibility of a university education was abandoned, but since it would have consisted of yet more classics with added mathematics, the loss was not greatly mourned.

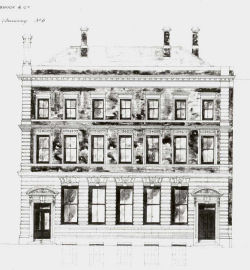

The bank of Robarts, Lubbock & Co., 15 Lombard St, London, in 1860. In 1914 it was absorbed by Coutts & Co. Image © Coutts & Co. 2013.

On the other hand, the responsibility thrust upon a teenager (the two partners died, and ‘he and I, with a worthy old clerk … carried on the business, so that my father and I could not be away together. I was at first of course very much at sea, and found the City very lonely’) must have been terrifying. His friend and biographer, Horace G. Hutchinson, believed that Lubbock’s self-discipline, and his remarkable ability to focus intensely on whatever task was before him, must have been developed at this period.

Lubbock divided his time between the needs of the bank (of which he became head on his father’s death), and the wider banking world, in which he was instrumental in modernising reforms, politics, the sciences, and popular writing. His scientific and historical interests were nurtured by Darwin and the circle of his friends,

This extract from Hutchinson shows the somewhat staggering list of friends who asked Lubbock to stand as MP for the University of London. He also acted as the University’s Vice-Chancellor from 1872 to 1880; his father had been the first Vice-Chancellor (1836–42).

and he was a great supporter of natural selection, using it as a tool for exploration of developments in prehistory. In 1865, he published Pre-Historic Times as Illustrated by Ancient Remains, in which he coined the terms ‘palaeolithic’ and ‘neolithic’, and in 1870 The Origin of Civilisation and the Primitive Condition of Man, which developed further the parallels between technological developments in prehistory and those in so-called ‘savage’ societies of his own day.

Sir John in his study at High Elms.

His entomological studies focused on ants, bees, and wasps. ‘When in the south of France in the spring, he had tamed a wasp, which he brought with him to [the British Association meeting at] Brighton. It had the honour of a leading article in the Daily Telegraph and in Punch.’ The Telegraph skit suggested that ‘next to Mr Stanley, this visitor might be called by far the most remarkable and best worth attention among all the assembled notorieties.’ Lubbock also kept a vivarium of ants on which he and his daughters made daily observations between 1874 and 1882, and he marked the passing of two of his queen ants, who lived for 14 and 15 years respectively.

Punch‘s 1882 caricature of Lubbock as a bee.

Charles Darwin’s funeral at Westminster Abbey, 26 April 1882. Lubbock was the instigator of a letter to the dean of Westminster suggesting that Darwin should be buried in the abbey, and was a pall-bearer, together with the dukes of Devonshire and Argyll, Lord Derby, T.H. Huxley, J.D. Hooker, J.R. Lowell (the American ambassador), William Spottiswoode, PRS, and Alfred Russel Wallace.

Lubbock’s first wife died in 1879, and in 1884 he married Alice Fox-Pitt, the daughter of General Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt-Rivers ( name-change related to a legacy), another Darwinist, whose development of the typology of artefacts, and excavations at Cranborne Chase, have led to the soubriquet ‘the Father of British Archaeology’. Alice was of the same generation as his six children from his first marriage. Hutchinson waxes lyrical about her ideal upbringing as a helpmeet for Sir John, and his preternatural sprightliness for his age, though more modern biographers have suggested that Alice would have married anyone to get away from her domineering father, but they do seem to have been mutually devoted, and had five children together.

In politics, he was both an MP and a member (and for many years chairman) of the London County Council. In Parliament, his chief concerns were for workers (as well as the Bank Holidays, he fought for statutory limits to the working day) and for the preservation of history: he introduced the 1882 Ancient Monuments Protection Act, which covered (in the first instance) 68 sites in Britain and Ireland, and led to the appointment of his soon-to-be father-in-law as the first Inspector of Ancient Monuments.

The antiquarian John Aubrey‘s plan of Avebury in 1663.

William Stukeley’s reconstruction of Avebury, 1743. Stukeley had earlier witnessed the efforts of local men to break up the standing stones by heating them in bonfires. (The name ‘Abury’ was in common use until the late nineteenth century.)

He purchased as much land as he could of the site of the Avebury henge, to preserve the stones from further destruction and from new homes for the growing village being built inside the rings, and, when created a peer in 1900, took Avebury as his title. He travelled widely, visiting France with Sir John Evans to meet Boucher de Perthes, encountering a rather bombastic Schliemann at Hissarlik and excavating himself at Bunarbashi, historically the most favoured possible site for Troy.

An 1810 sketch of the ancient mounds at Bunarbashi, by Sir William Gell.

He wrote best-selling books on the pleasures of life, the use of life, and the beauties of nature – he claimed no originality for these, but published ‘hoping that the thoughts and quotations in which I have myself found most comfort, may perhaps be of use to others also.’

Baron Avebury in old age.

And in addition he corresponded with hundreds of people on all sorts of topics, including Thomas Hughes (of Tom Brown’s Schooldays) on the need for scrubbing clean the Uffington White Horse, John Ruskin on aphids, Cardinal Manning on social problems, Randolph Churchill on bimetallism, and G.G. Stokes on the mathematics of proportional representation in elections.

The Uffington White Horse, now nicely scrubbed up.

Oh, and he spent some time teaching Van, his poodle puppy, to recognise flash cards, but felt it was unkind to keep a dog in London, and so sent him back to Kent and gave up the experiment.

Caroline

Pingback: The Legacy of Sir J.E. Smith | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: The Holwood Oaks | Professor Hedgehog's Journal